The writing process consists of many stages. According to most Language Arts and Writing curriculum experts these stages include pre-writing, drafting, revising, editing, and publication. (On a side note, I want to add that these stages aren’t always linear and are often repeated multiple times within a single manuscript.) My least favorite of these stages is editing/ revising, not because I have issues with grammar or sentence structure, but because it’s time consuming and forces me to drink too much caffeine. Although I detest revising and editing, I want to focus on that stage of the writing process today.

linear and are often repeated multiple times within a single manuscript.) My least favorite of these stages is editing/ revising, not because I have issues with grammar or sentence structure, but because it’s time consuming and forces me to drink too much caffeine. Although I detest revising and editing, I want to focus on that stage of the writing process today.

I’m currently in the process of revising and editing my second book. If I survive this process without losing all my hair I will be pleasantly surprised.

I want to start off with a personal disclaimer based on my experience as both a teacher and a writer. Everything we were taught and still teach kids about writing does not apply to the real world of fiction. Every English teacher is cringing as I say that. The classic “said is dead”. The five sentence paragraph. Every sentence must have a subject and predicate. Story boards and planning sheets. Topic sentence and supporting details. All of those strategies and techniques are great if the only thing you ever plan to write in your life is a research paper. For fiction, the rules don’t always apply.

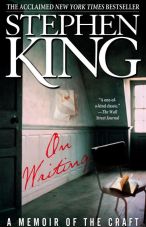

Over the years I’ve read tons of advice about writing, and listened to only a fraction of it. I’m the kind of person who tends to take advice from people who have walked in my shoes. When it comes to writing, I’m going to listen to people who are successful in the business. I’ve read several books about the craft of writing. Among my favorites are Chuck Wendig’s The Kick-Ass Writer, Stephen King’s On Writing, and Self-Editing for Fiction Writers by Renni Browne and Dave King. Stephen King mentions another one called The Elements of Style written by William Strunk Jr. and E.B. White. I have not read this one yet, but it is the next writing book on my “to read” list.

These books were written by experts in the field and offer tons of advice about the craft of writing. If you haven’t read them, I highly recommend that you do.

Stephen King said it best. Write with the door closed, rewrite with the door open. What he meant by that was your first draft should be written to get the story out there. Close the door to eliminate distractions and just write. When you revise and edit, you’re clarifying meaning for your reader, smoothing out details, opening the door for them.

Stephen King said it best. Write with the door closed, rewrite with the door open. What he meant by that was your first draft should be written to get the story out there. Close the door to eliminate distractions and just write. When you revise and edit, you’re clarifying meaning for your reader, smoothing out details, opening the door for them.

First drafts are crap. Every writer will tell you that. We all write chapters we don’t want published, but that’s what revising and editing is for. When you are ready to re-read your manuscript and trudge through the revising and editing process, please keep one thing in mind: the worst thing you wrote is better than the best thing you didn’t write.

Let’s start by clarifying the difference between revising and editing. Revising is adding/removing words, sentences, or paragraphs, changing a word or placement of a word (or entire chapter), and substituting words or sentences for new ones. Editing involves capitalization, sentence structure, spelling, and punctuation.

Now that that’s been clarified, we can get down to business. I am not a writing expert and in no way do I claim to be. But I have learned a few things from the experts, and from personal experience, that I think are worth sharing.

1. Said is not dead. Back in Elementary School, Middle School, and High School we were all given extensive lists of alternative words for said. The funny thing about that is in the world of fiction writing, editors want you to use said. In On Writing, Stephen King even recommends he said, she said. Nothing more. Go figure.

2. Avoid dialogue tags. This is where the phrase said is dead would apply. Don’t write “Let’s go to the park,” Billy said. Instead use a beat. Here’s an example. Billy picked up his basketball and held it under his arm. “Let’s go to the park.” This shows action, and based on that action, I know Billy is the one speaking. Use of a dialogue tag may sometimes be necessary to clarify who is speaking, but when you use one, stick with said.

3. Read dialogue out loud. Does it sound genuine? Does it sound like something your character would say? If your character is a surfer, does he or she speak in surfer slang? Each character has his or her own voice. The words that come out of your character’s mouth should reflect that voice.

4. Avoid as and -ing. Example: As I walked down the street, I saw a dog with a bone between his paws. Walking down the street, I saw a dog with a bone between his paws. Stephen King suggests you do neither of the above. Instead get to the point and simply say, I walked down the street and saw a dog with a bone between his paws. He’s written and sold countless best selling novels. Might not be a bad idea to consider his advice.

5. Along the same lines, cut the fluff. Don’t try to fancy up your writing with big words your reader won’t understand. The purpose of fiction is to tell a story, not to show off your extensive vocabulary. Use the first word that comes to mind. If you later think of a word that better describes what you want to say, then by all means change it. As the writer you have every right to change, add, and delete all you want. But usually your first instinct is the best.

6. Grammar. You don’t have to be a grammar Nazi, and language doesn’t always have to be dressed in a suit and tie. In fact, sometimes grammatically proper sentences can stiffen a line. It’s ok to use fragments and omit a comma if you want the line to be read without a pause. It’s ok to have a one word paragraph. Really. It is. But you need to know enough about grammar to sound intelligent.

7. Go with the flow. Your story telling should be smooth, not choppy. When you re-read, listen to the beat. Can you hear the rhythm?

8. Proportion. Vary sentence length. Alternate between narrative and dialogue. Write intense action then give your reader some time to breath with a more relaxed scene before you move into action again.

9. Show, don’t tell. Let your characters tell the story through their actions and dialogue. Don’t tell me Mary is sad. Show me her glossy eyes and quivering lip. Let me hear her sobs and feel her tear-soaked shirt sleeve. Give your reader details, but not so many that you flood the story and disturb the flow. Show only what your characters see. Let the reader imagine the rest.

10. To steal a quote from Stephen King, The road to hell is paved with adverbs. He didn’t run quickly, he sprinted. The use of adverbs means you didn’t choose the right verb. Find a stronger verb. Not a fluffy one, just a stronger one.

11. If you don’t need it, cut it. Stay on target. If a line, sentence, paragraph, scene, or chapter doesn’t move the story forward, get rid of it. Cut unnecessary characters. Cut unneeded dialogue. Revising and editing will not kill you. It may kill some of your characters, but it won’t kill you.

11. If you don’t need it, cut it. Stay on target. If a line, sentence, paragraph, scene, or chapter doesn’t move the story forward, get rid of it. Cut unnecessary characters. Cut unneeded dialogue. Revising and editing will not kill you. It may kill some of your characters, but it won’t kill you.

Revising and editing is painstakingly time consuming and often frustrating. You slaved for months to write this manuscript and putting it on the chopping block is hard. Believe me, I know. But if you take the time to revise and edit without mercy, your writing will reap the benefits.

I want to close with one last remark. Find your voice. Attempting to copy another writer is fake and often forced. You have a voice and you have a style all your own. Find it, use it, refine it. It’s your story. Don’t let anyone else hold the pen.

I’m impressed with the editing tips!

LikeLike

My teachers, for some reason, went light on the writing advice, and I thank them all, but I do remember being told to write a topic sentence for each paragraph. It paralyzed me until some internal switch flipped and I ignored the advice and started writing again. Couldn’t do it then; can’t do it now–and no longer see any reason to.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Novel-Writing Process: From Outline to Print – Allen Writing